The Missing Piece

"As renewable sources of power become more and more important during the energy transition, stakeholders will look towards technologies such as hydrogen for solutions to the intermittent nature of these sources. At a time when many countries are trying to break away from a reliance on fossil fuels, storing electricity via hydrogen could help plug the inevitable gaps that this will leave in baseload generation." - Ellie Chambers, Editor of European Daily Electricity Markets, ICIS

Decarbonisation cannot be achieved with renewables alone. There will be days when the sun does not shine and the wind does not blow, but we will need to keep our lights on and our homes warm. Industry, the powerhouse of net-zero technology, cannot run exclusively on electricity. Hydrogen answers these problems and more, supporting decarbonisation of hard-to-abate sectors. It offers all the benefits of natural gas, like flexible power generation and ease of storage, but when burned it emits zero carbon. It is a key feedstock in refining processes and fertilisers and can be used in steel production. And while cars and small vehicles can be suitably replaced at consumer level with battery technology, the scale of aviation, shipping and heavy goods vehicles requires a molecule, such as hydrogen.

The applications of hydrogen for decarbonisation are vast, and as a result the where and when hydrogen will be used differs slightly from country to country. Despite this, key uses are often reduced to three areas of demand: industry, power generation when renewable output is low, and transportation. Whatever the shape of future hydrogen demand, one theme remains consistent across governments all over the world: hydrogen will play a critical role in achieving net-zero emissions by 2050.

The targets set by governments for the use of hydrogen on the path to net-zero puts an onus on energy, industry and transport to adapt to facilitate the desired goals. This is because hydrogen is rarely used in transport and energy, and of the hydrogen currently produced globally, the vast majority has a negative impact on the environment. This is because it is produced using fossil fuels, such as coal and natural gas, without carbon capture and storage technology. For example, in 2020, 90 million tonnes of hydrogen was produced globally, yet for every tonne of hydrogen produced, 10 tonnes of carbon dioxide was released.

Businesses therefore face challenging investment decisions and changes to their current means of operating. Practices and products that were once accepted are no longer consistent with a net-zero future, and instead, new production methods and supply chains must be established. All of this means the integration of climate-friendly hydrogen into business models at a cross-sectoral level is now a requirement in many countries all over the world.

Building the hydrogen market

"The hydrogen and natural gas markets will become closely correlated in the years ahead both in terms of wholesale prices and demand/supply dynamics, as European players increasingly look at hydrogen as a key commodity reducing carbon emissions in the energy sector. As such, stakeholders involved in the European gas markets and energy policy makers will need to increasingly factor in what hydrogen will mean for natural gas demand and supply and how it can be used next to methane during the energy transition." - Alice Casagni, Editor of European Spot Gas Markets, ICIS.

Market participants require certainty if environmentally-friendly hydrogen is to be produced at scale and adopted across different regions of the global economy. Current and potential offtakers need to understand production costs and market drivers for low-carbon and renewable hydrogen if they are to integrate it into their supply chains. Producers, on the other hand, need to know what market opportunities are out there, and how much demand for hydrogen will there be as countries slowly scale up efforts to use it in different sectors. While both consumers and producers need a central market value if they are to invest in new hydrogen technologies.

As well as certainty, the market requires transparency. Much of the hydrogen produced today is used locally, and the price at which it is sold is rarely known to other market participants. Such a lack of transparency often occurs in emerging markets, for example it characterised the initial development phase of the European gas markets towards the end of last century. During the early 1990s, ICIS led European energy markets by being the first independent information provider to report price assessments for British gas beaching points.* Our price reporting gave gas traders a reference point, a fair and unbiased value from an independent source that reflected changes to patterns of supply and demand. This work led to the development of Europe’s first liquid gas hub, the British NBP.

The transparency achieved through our natural gas assessments supported a shift away from long-term contracts and enabled progress towards the liberalisation of a liquid spot market. The reactionary nature of spot markets meant traders could secure volumes of natural gas as they were needed, ensuring an efficient use of resources.

From concept to reality

"While there are technical differences in how hydrogen and natural gas are transported, hydrogen developers may look to learn from the evolution of LNG markets. LNG growth came through a combination of major investment, technological innovation and the desire to connect markets regionally and globally. Natural gas is a transition fuel for today and hydrogen is a clean fuel for tomorrow. But both commodities can co-exist over the coming years with both playing a part in reducing emissions in national power networks and in shipping." - Ed Cox, Global LNG Editor, ICIS.

Using hydrogen as a key to decarbonisation is a relatively new concept. It was only in 2020 that the European Commission published its hydrogen strategy, while it was the end of the third quarter of 2021 when the UK government announced its own. Timelines within these plans are also short given the scale of the challenge to integrate hydrogen in an environmentally friendly way into new and existing markets. The commission’s first target for the use of renewable hydrogen in industry is 2024 – just two years away.

Most strategies have key targets in place for 2030, making this decade crucial for the future of energy and indeed our planet. This means governments, regulators and energy companies must decide upon the rules of play for the future hydrogen market in the next few years. Business leaders are therefore faced not only with assessing the business case for hydrogen based on cost-benefit analysis, but also with keeping up to date with conversations that could move the goalposts. With each new policy point decided for hydrogen, a company’s map to 2050 might change.

To meet climate goals, organisations have to embody a growth mindset that can react to a fast-changing environment. Adopting hydrogen to the scale and of the quality required by national and international policy will need investment. But this investment comes out of necessity: the only market of the future will be one that supports net-zero.

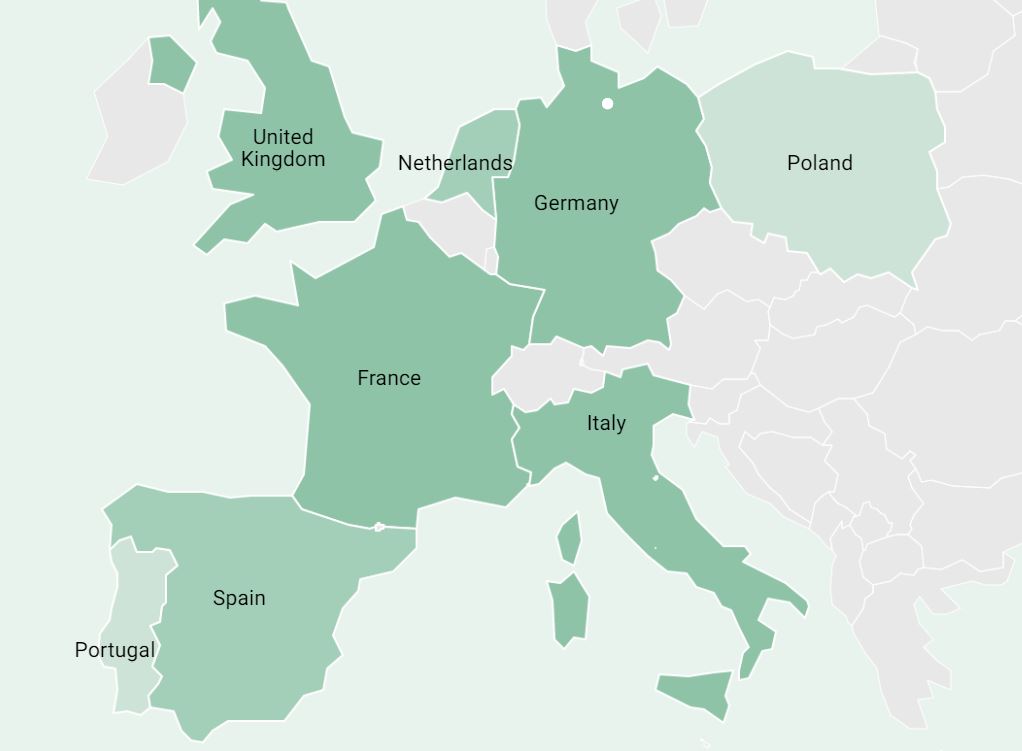

European National Hydrogen Production Capacities by 2030