Author: Tom Brown, London

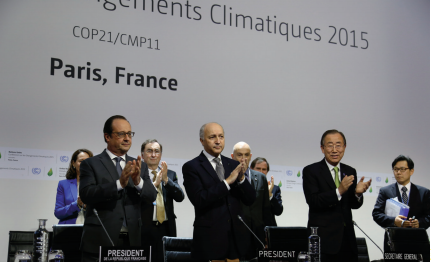

After several years of negotiation, the Paris Climate Conference (COP21) that took place in November last year is widely seen by industry and policymakers alike as a genuine milestone in global emissions-reduction accords.

“I think it’s widely recognised that the COP21 in Paris was a breakthrough in terms of climate conferences,” says Marco Mensink, director-general of Brussels-based chemicals industry body Cefic. “The agreement reached was what people hoped for in Copenhagen a few years back, and in this case the EU was able to take a lead which it wasn’t able to before in getting the deal brokered. “At the time of the COP in Copenhagen, the US and China pretty much went off and left Europe standing there in the cold and made a deal. In this case Europe was actively brokering a deal in Paris,” he adds.

The Paris conference represented a tipping point, with the US government at the time less than 12 months away from a change of administration, and China sufficiently concerned about air quality in its cities that it was finally willing to sign up to a concrete emissions-reduction target.

“China and the US are two of 148 countries, representing 87% of global emissions, that signed up to intended nationally determined contribution (INDC) commitments to reduce greenhouse gases (GHGs) to cut emissions – a number that has risen since then to 179.

China has committed to reach its emissions peak by 2030 – and earlier, if possible – and cut back from there, while the US committed to cutting emissions by 26-28% by 2025.

A DIFFERENT APPROACH

A key factor in securing their support was the shift from top-down agreements, where a target would be set centrally, to a bottom-up approach where countries would decide their commitments. “The big difference in the negotiations was going from a top-down climate agreement, to a bottom up process, which is what the US and China wanted in the first place,” says Mensink.

The shift allows countries to determine the most achievable approach for their GHG reduction targets. While this freedom allowed an agreement to be reached, whether that will lead to the capping of global warming to 2030 at 1.5 degrees remains to be seen.

“The Chinese leaders have said very directly that they will do what is appropriate for China, and we have the feeling that other global actors will be focusing on how it fits also to their economic development,” says Brigitta Huckestein, senior manager for energy and climate change at BASF.

The European chemicals industry is a producer of climate change solutions and a heavy greenhouse gas emitter, and Cefic president and Solvay CEO Jean-Pierre Clamadieu underlined the challenges and opportunities presented to the sector by the Paris accord at the body’s annual meeting last year.

“COP21 is an important event for the chemical industry. We are both large contributor to emissions, we are large users of energy, but we are also a very important provider of technologies and solutions when moving into a low-carbon economy,” he said when speaking in Brussels last year.