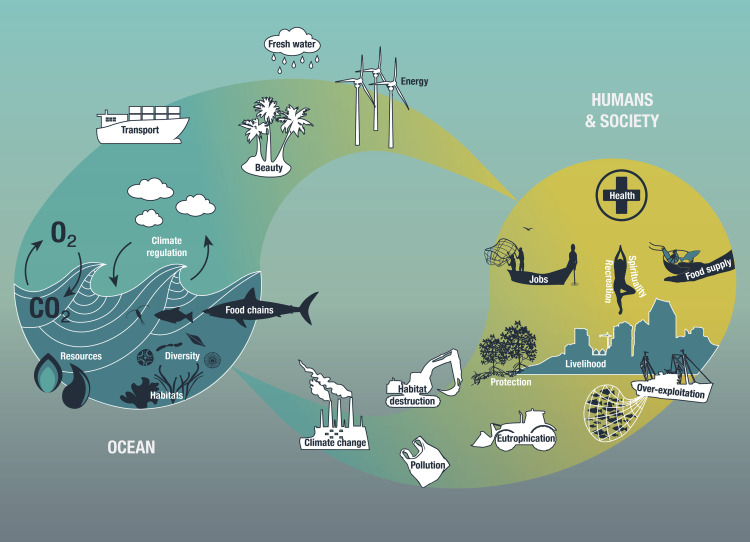

Oceans and seas play a vital role in the context of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as they significantly contribute to the Earth's biosphere's health and the global economy. They are critical to sustaining life on earth, acting as a major source of food and oxygen while also serving as natural carbon sinks that mitigate climate change impacts. SDG 14, "Life Below Water," explicitly acknowledges the importance of conservation and the sustainable use of the world's oceans, seas, and marine resources.

Oceans absorb about 30% of carbon dioxide produced by humans, buffering the impacts of global warming. However, this process has implications such as ocean acidification, negatively impacting marine biodiversity and ecosystems. These impacts, coupled with unsustainable fishing practices and pollution, threaten the health of our oceans and seas. SDG 14 sets targets to prevent and reduce marine pollution of all kinds, sustainably manage and protect marine and coastal ecosystems, and regulate harvesting and end overfishing to restore fish stocks to sustainable levels.

Oceans also support economic wellbeing. Over three billion people depend on marine and coastal biodiversity for their livelihoods. By protecting oceanic ecosystems, the SDGs also support SDG 1, "No Poverty," and SDG 8, "Decent Work and Economic Growth." Furthermore, the oceanic routes are critical for global trade, supporting SDG 9, "Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure."

Furthermore, by implementing strategies for cleaner and more sustainable use of oceans and seas, it can also contribute to SDG 13, "Climate Action." For instance, developing and implementing new technologies to harness energy from waves and tides can promote renewable energy usage and reduce reliance on fossil fuels, aligning with SDG 7, "Affordable and Clean Energy."

Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part - C: Toxicology and Pharmacology, Volume 235, September 2020

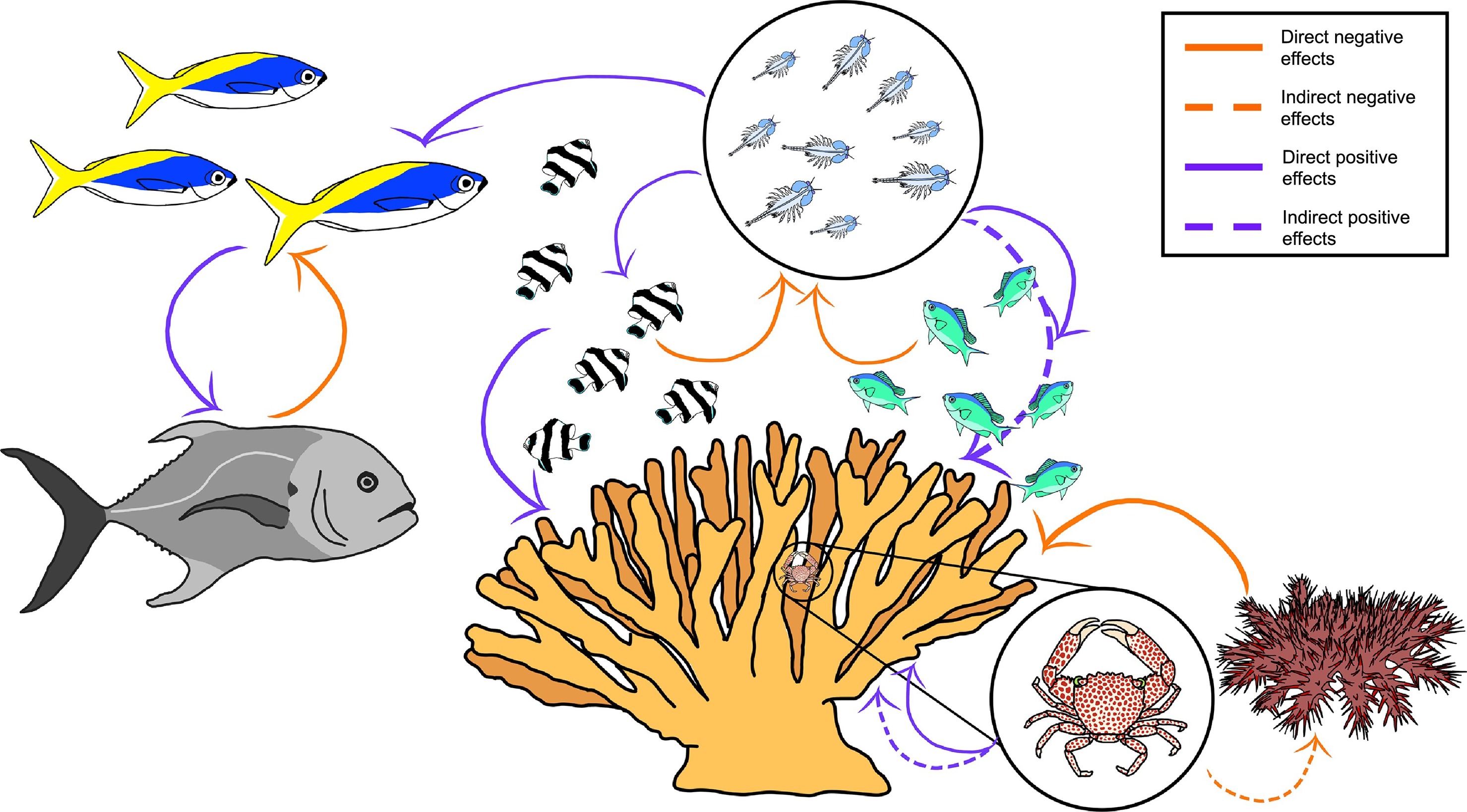

Ecology plays a central role in the management and conservation of ecosystems. However, as coral restoration emerges as an increasingly popular method of confronting the global decline of tropical coral reefs, an ecological basis to guide restoration remains under-developed. Here, we examine potential contributions that trophic ecology can make to reef restoration efforts. To do so, we conducted a comprehensive review of 519 peer-reviewed restoration studies from the past thirty years.

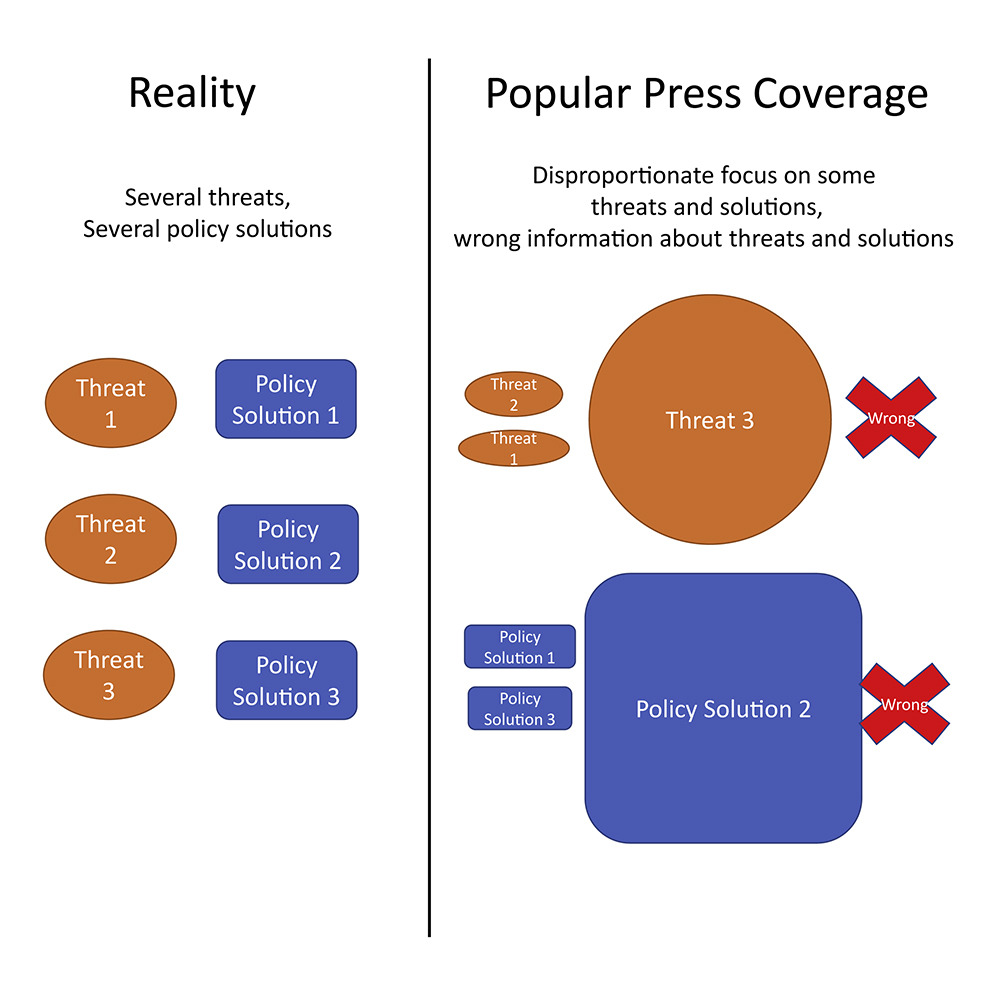

Protecting the ocean has become a major goal of international policy as human activities increasingly endanger the integrity of the ocean ecosystem, often summarized as “ocean health.” By and large, efforts to protect the ocean have failed because, among other things, (1) the underlying socio-ecological pathways have not been properly considered, and (2) the concept of ocean health has been ill defined. Collectively, this prevents an adequate societal response as to how ocean ecosystems and their vital functions for human societies can be protected and restored.