Forests, representing an integral part of the planet's biosphere, play a significant role in achieving the United Nations' Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). They function as extensive carbon sinks, absorbing greenhouse gases and contributing to SDG 13 (Climate Action), and they provide a wealth of biodiversity, aligning with SDG 15 (Life on Land).

Forests are indispensable in fostering clean air and water, acting as natural filters, thus contributing to SDG 6 (Clean Water and Sanitation) and SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being). They are also a vital source of food, medicine, and raw materials for billions of people, directly supporting SDG 1 (No Poverty), SDG 2 (Zero Hunger), and SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth). Indigenous and local communities are often dependent on forests, tying in with SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities) and SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities).

The responsible management of forests promotes SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production) and also creates opportunities for SDG 4 (Quality Education), with forest-based learning enhancing environmental literacy. Lastly, forests serve as potent buffers against natural disasters, fostering resilience and adaptation in the face of changing climate conditions, thereby contributing to SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities). As custodians of biodiversity and vital ecosystems, forests are fundamental to the holistic accomplishment of the SDGs. They embody the interconnectedness of these goals, demonstrating how progress in one area can stimulate advancements in another.

Understanding this interrelation and harnessing it for sustainable development policies is a cornerstone of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. By maintaining and restoring forest ecosystems, we are not just preserving landscapes; we are making a commitment to the sustainability of our planet and future generations.

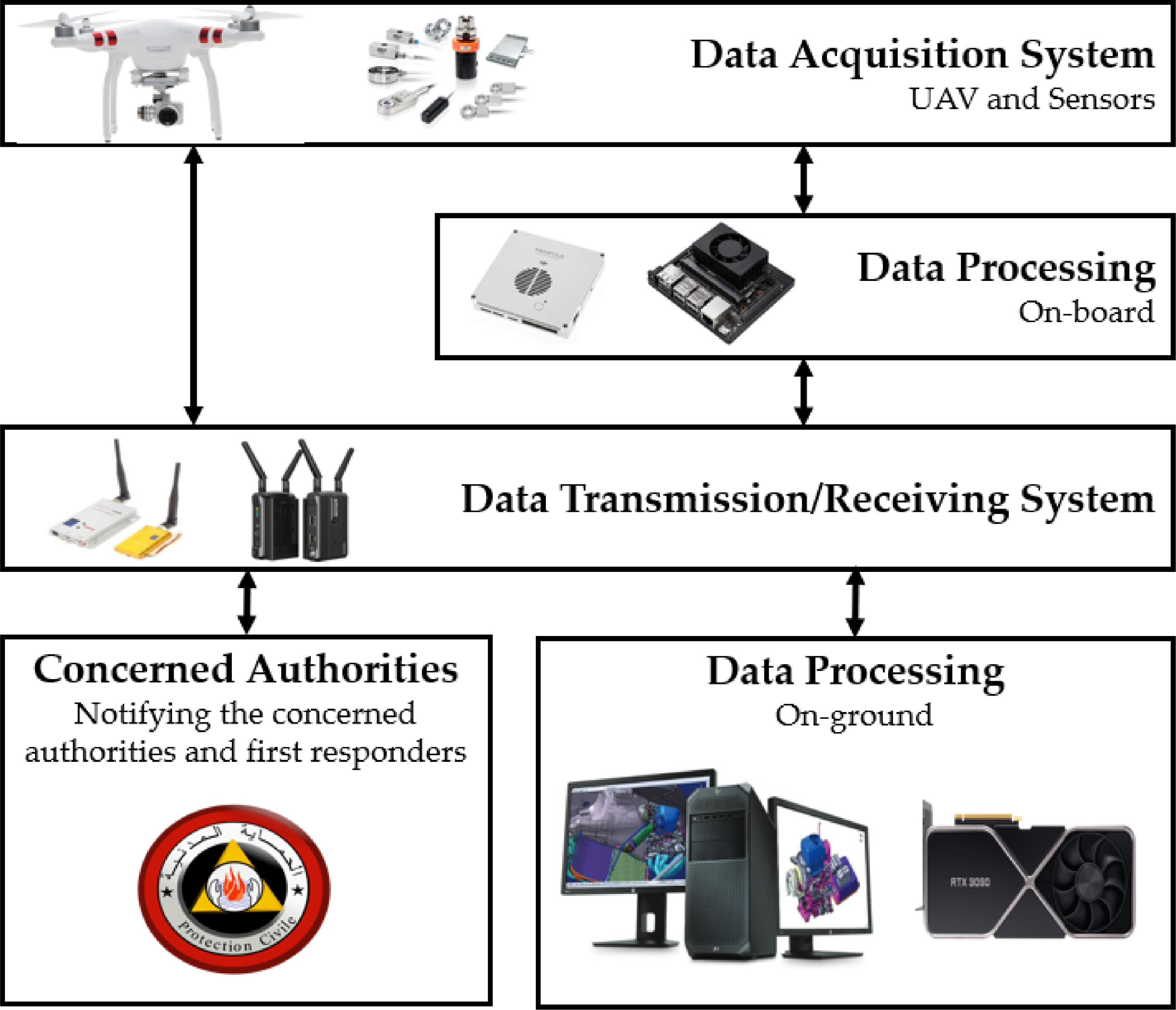

Wildfire is one of the most critical natural disasters that threaten wildlands and forest resources. Traditional firefighting systems, which are based on ground crew inspection, have several limits and can expose firefighters’ lives to danger. Thus, remote sensing technologies have become one of the most demanded strategies to fight against wildfires, especially UAV-based remote sensing technologies. They have been adopted to detect forest fires at their early stages, before becoming uncontrollable.

Mangrove-dominated estuaries host a diverse microbial assemblage that facilitates nutrient and carbon conversions and could play a vital role in maintaining ecosystem health. In this study, we used 16S rRNA gene analysis, metabolic inference, nutrient concentrations, and δ13C and δ15N isotopes to evaluate the impact of land use change on near-shore biogeochemical cycles and microbial community structures within mangrove-dominated estuaries.

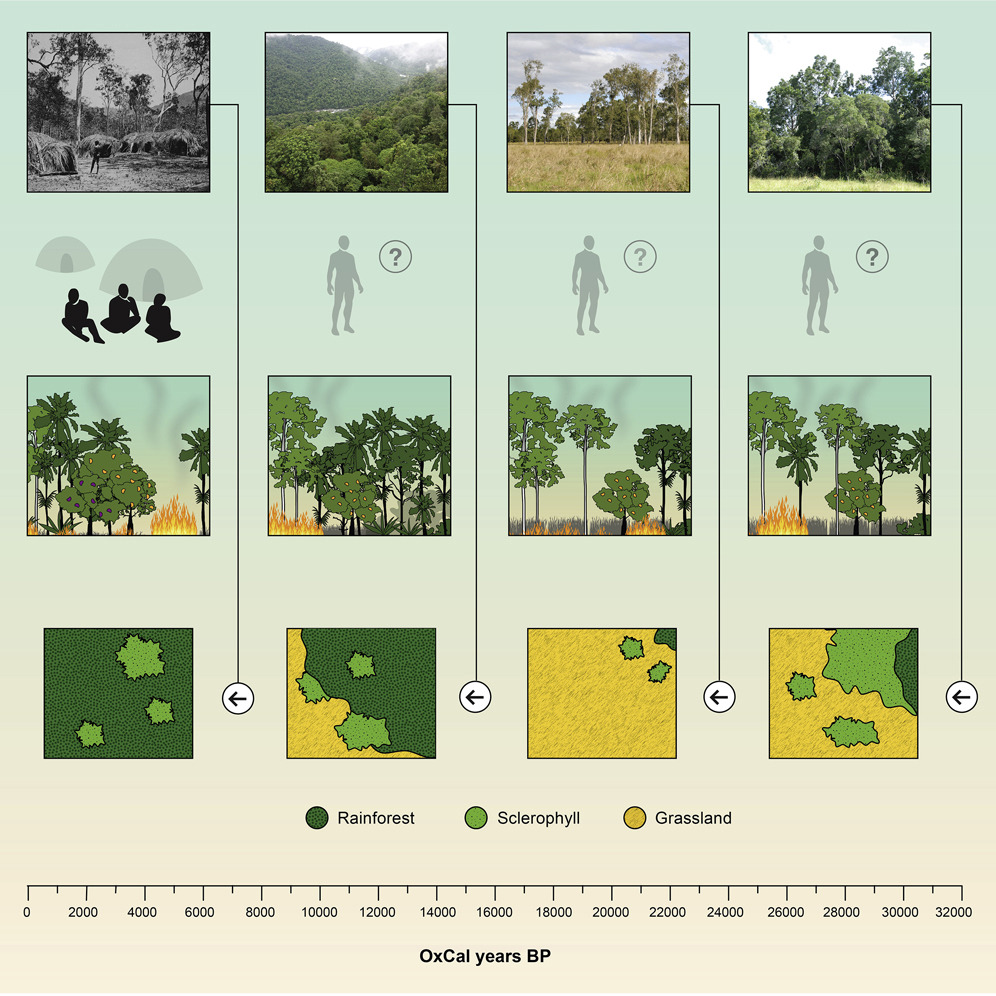

World Environment Day is the most renowned day for environmental action. Since 1974, it has been celebrated every year on June 5th, engaging governments, businesses, celebrities and citizens to focus their efforts on a pressing environmental issue. In 2020, the theme is biodiversity, a concern that is both urgent and existential. Recent events, from bushfires in Brazil, the United States and Australia, to locust infestations across East Africa – and now, a global disease pandemic – demonstrate the interdependence of humans and the webs of life in which they exist.

The Paris Agreement to keep global temperature increase to well-below 2 °C and to pursue efforts to limit it to 1.5 °C requires to formulate ambitious climate-change mitigation scenarios to reduce CO2 emissions and to enhance carbon sequestration. These scenarios likely require significant land-use change. Failing to mitigate climate change will result in an unprecedented warming with significant biodiversity loss. The mitigation potential on land is high. However, how land-based mitigation options potentially affect biodiversity is poorly understood.